In the spring of 2007 two events would drastically change the course of my life. I was expecting one of them but the other came as a surprise.

Some months previously I had started attending a yoga class in my local gym. It was a ‘led’, or counted Ashtanga session, the kind you will find on triyoga’s schedule. It wasn’t the very first class I tried but it was the one I fell for, hard and fast. I was a keen swimmer and the ‘vinyasa’ system of matching breath to movement in a precise, rhythmic order felt familiar enough to lure me in. I soon became a regular and, as much as I enjoyed the dynamic intensity of the sequences, I was mostly drawn to the calming, grounding effect of counting and regulating the breath.

I had what most people would call a stressful job. Although I loved every minute of it. I was a chef. I have always had a keen (some might say nerdy) interest in food and cookery. Somehow, I’d managed to pass off my hobby as my career.

No matter how much you love being at the stove, a commercial kitchen is a busy, clamorous space. It doesn’t suit the shy and retiring type. For this reason, too, I became increasingly fond of my time on the mat. Here was a world I hadn’t really witnessed before, where intensity and concentration didn’t require fire and cast iron, flames and raised voices.

Life threw me a bit of a curveball when three friends and I got the chance to open a restaurant in London’s West End. The scruffy, quirky site was ringed by theatres but it was just far enough off the beaten track of Leicester Square and Covent Garden to be affordable. Our neighbours were a fashionable milliner and an artisan florist. We took the plunge without truly realising how busy we would get and how fast it would happen. We still had no name and no signage when we threw open the doors in April 2007. People found us anyway and to this day our address is still our ‘name’ – 32, Great Queen Street.

Nothing can fully prepare you for the opening of a restaurant. It is a bit like launching one of those West End shows (except that the script is never quite the same each night). A lot of the work is hugely enjoyable: The sheer physical demands of busy, adrenaline fuelled services, the close camaraderie and (mostly) smiling customers is a heady mix. It’s not all fun and games: deviant equipment, disobedient ingredients or (worse still) missing deliveries and staff can jar your nerves on a daily basis. Sometimes everyone seems to arrive for dinner at once, no matter what time they booked. Sometimes everyone asks you about everything because owning the place makes you the oracle. There is no hope of sticking to a set routine. Looking back I wouldn’t change a thing. At the time, though, part of me pined for that sacred yoga class from which I was more and more absent. Same day, same time, same place, every week? Impossible!

Like most people back then, I had never heard of the ‘Mysore’ or self-practice method. And when I did (thanks to Alex, that very kind teacher at the gym), I was quite daunted by the idea. Outside of India most people encounter the asanas of Ashtanga yoga in a led class. Only a very experienced or athletic person might describe this kind of class as easy (and thinking about it, I’ve yet to meet him or her). The pace and intensity of led Astanga classes is governed by necessity. Everyone starts and finishes at the same time. It’s easy for the uninitiated to think that a Mysore class will be all the above and more because they are somehow, magically, supposed to know what to do.

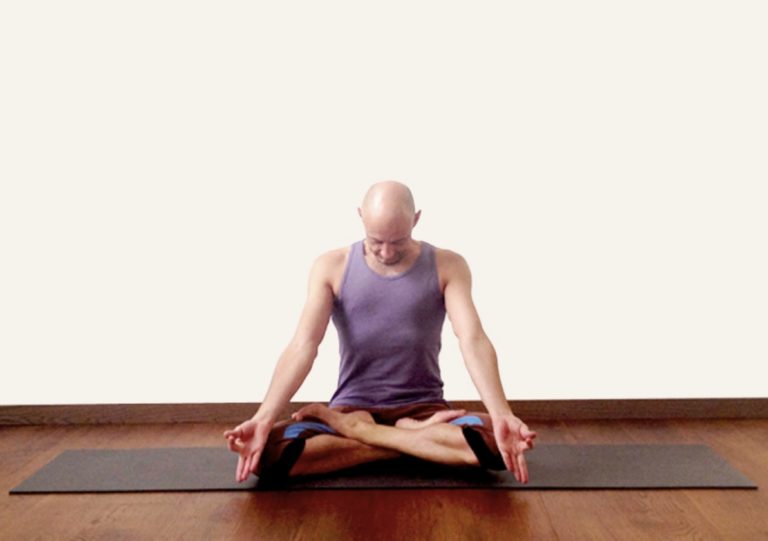

In fact the opposite is true. There is probably no more simple or straightforward asana practice than beginner’s Astanga. In traditional studios or shalas, first timers simply learn the vinyasa of surya namaskar (sun salutes). These are committed to memory by repetition and, once the student has done enough of them he or she is taught three seated postures, which ‘finish’ the practice and prepare the body for a rest.

The surya namaskars are a very complete practice in themselves. They demonstrate perfectly the principle of vinyasa and provide the building blocks of tristhana: the three places of attention (breath, movement and visual focus) which make Astanga yoga such a powerful, dynamic form of meditation. This is important to remember because some people transitioning from led classes to self-practice feel they are being ‘pulled back’ or restricted. In fact, a less-is-more approach to asana lays the foundations of true self-sufficiency. Each time you leave a Mysore class you should be able to remember everything you did there. That way you can practice wherever you are. It’s also easier to shift from one or two led classes here and there, to a regular practice if that practice is shorter and less confusing.

In the traditional setting, the standing sequence is taught directly after learning the surya namaskar, with one or two asana added at each session. The standing series is similar to the surya namaskar in that, without too much in the way of complexity, it allows students to focus on learning the order in which the asana should be practiced. I say these asanas lack complexity but they are not easy! If you’re not familiar with a posture like uthita hasta padangustasana It’s quite an eye opener to discover that raising one leg even a few centimeters off the floor without involuntarily hopping around on the other is a big challenge.

The standing sequence has myriad benefits, some more tangible than others to new students. It strengthens and tones the legs, the spine and the muscles of the core. It is particularly beneficial to anyone with lower back, hip or knee pain. It works wonders on flat feet but, most of all, it does what it says on the tin and teaches you to simply stand up properly. I should know because in those early days of the restaurant it pretty much was my practice.

I was visiting Astanga yoga London, a shala entirely devoted to Mysore, whenever I could. The morning and evening sessions there are run separately but my teachers Hamish Hendry and Roberta Giannotti were taking a keen interest in this strange man who wanted to work 60 hours a week or more and learn Astanga yoga. I know what you’re thinking, because when I write this down it sounds a little unhinged.

My working day was anything but nine to five. If I was on a lunch shift it would begin at 7am and (with a bit of luck) end at 5ish in the afternoon. At that time, I would go and practice with Roberta before returning to the restaurant and making sure the dinner shift was ok. A dinner shift began at 4pm and ran until midnight. On those days I would practice at home when I got up. I visited Hamish in the morning on my days off. There is another type of shift called a double, which anyone who isn’t a chef thinks is awful. Most chefs love it (we are very strange people). Lunch and dinner. 7am to midnight. The thrill of a double is hard to describe. It’s partly about seeing the whole arc of a day-in-the-life of your restaurant. On those days I would get up, sit on my mat for ten minutes looking at the tip of my nose, then go to work.

One of the reasons I was so determined to practice around my schedule was that it felt medicinal. Lots of chefs suffer from aches and pains here and there. Lower back and knee pain is common but so is tension in the shoulders (from hunching over benches) or aching wrists (from endless chopping.) Hamish had worked in kitchens and was brimming with advice on how deal with what I called ‘chef legs’. My thighs would be stiff and sore on my days off or shaking like jelly after a tough shift. Learning how to stand began to change this very quickly. Within months I was working free from pain. More importantly, the practice was a powerful way to quell the inevitable anxiety that came with running a new business.

The key to all this was sticking to a rule which was ‘practice come what may’. Work was a series of to do lists and deadlines. So I had to make sure yoga was something very different. The only thing that had to happen was some form of practice. If tiredness or lack of free time meant it had to be short and simple, then so be it. I had a little invocation I would recite under my breath just before chanting the opening mantra. I’d say…

“I will practice without reserve or restraint

I will practice without ambition or striving.

I will greet the sun and see what happens.”

I could never have really imagined what was going to happen in the long run. But if we are honest with ourselves which of us can?

As the years passed and my routine settled I found a more regular slot for my practice. It became, as it is now, the first thing I do every day. The restaurant had produced a young, talented team who were chomping at the bit to be head chefs and managers. As the partners stepped back to let this happen there was talk of other projects. Something had shifted in me to the point where, after decades at the stove, I wanted a little quiet time. I thought a bit about studying. And then I thought a lot about going to Mysore. The practice had done something profound for me, so why not visit the source? I made the first of what would become several trips in 2010.

This is not the story of how I left my old job and became a yoga teacher because that’s not what really happened. But it’s worth explaining why, when the opportunity arose, I felt compelled to share some of my experience with others on the path.

I never entertained the idea of teaching. It sort of crept up on me. And when it did, my reasoning was simple. I look at yoga much as I do at cookery. It’s a life skill, a life saving skill. Anyone can do it. It’s not artistry, it’s a craft. The first task of a teacher is to make people want to practice. After that he or she must make sure that practice is nurturing and sustainable.

This might sound like stating the obvious. But a surprising number of people are put off traditional Astanga yoga (or try it for a time and then drop it) because they feel it asks too much from them. There are myriad reasons for this but one common mistake is to treat the practice like a sport. The physicality of the asana practice makes a great exercise routine. But to truly benefit from it, you need to switch off the achieving part of your brain. You’re never trying to “beat your personal best” or “break through your wall”. You don’t have to be good at asana for it to be good for you.

Switching off our “achieving” self is never as easy as it sounds. Sometimes I manage it, often I don’t. But here are some tips and bits of wisdom I’ve picked up along the way. They inform the way I try to practice and teach.

1. Never forget it’s therapy. The Westernised names people use to describe the sequences or series of asanas are not always that helpful. Calling them primary, intermediate and advanced instantly pushes our achievement buttons. First, second and third (the order in which they are taught) is slightly better. It’s important to remember that we learn primary series first not because it’s the easiest but because it’s the most important. The Sanskrit name for primary series is yoga chikitsa which, literally translated means ‘yoga therapy’. According to Paramaguru Sharath Jois of the KPJAYI in Mysore it’s the only series you ever need to learn. If you do practice beyond primary, remember to return there whenever you need to. In a nutshell that’s at least once a week but also whenever life makes great demands of you, as it often does. Emotional upheaval, travel, even a heavier than usual work load or increased family commitments should be seen as an opportunity to get back to basics and feel the ground beneath your feet.

2. Don’t judge. Your practice space, whether public or private, should be a place free of judgment. This relates strongly to the need to practice without striving for anything. You must be able to let yourself off the hook on those days when you feel tired, stiff, sore, clumsy…things it’s almost impossible to avoid from time to time. A good teacher will not be judging your practice on how good it is. So neither should you. Try to avoid judging yourself by the standards of other people’s practices as well. In the Mysore room no one is doing better (or worse) than anyone else. Your practice might well be different to the person next to you because, even though we are all following roughly the same path, certain parts of the journey are tweaked to meet individual needs and circumstances. My teacher Hamish sums this up with a very neat phrase, “the only bad practice is no practice.”

3. Trust yourself. Sometimes you will have a strong sense of what your body (or mind) needs when you get on the mat. You might want to shorten or soften your practice. It’s easy to think that not doing everything you’ve been taught is some kind of cop out. It isn’t. There are many well-recognised short forms of the practice. If you’ve been practising a while you might have forgotten how complete a few repetitions of surya namaskar and the simple postures of the finishing series once felt. It’s always okay to pull back. It’s never a good idea to ignore pain, fatigue or distress.

4. Trust the practice. Because we sometimes invalidate short or modified forms of the practice it’s easy to talk yourself into staying away from the mat when anything is wrong. However self-conscious an injury or other condition makes you feel, it’s better to practice. There is always a way to do this without aggravating whatever is wrong. A good teacher will guide you through such times. The practice can aid healing if it is approached the right way.

5. Last but not least! It’s always okay to laugh at yourself. Especially if you wobble or fall over. It’s always okay to cry, too. You will not be the first to do it. It’s always okay to be you!

If you are thinking of joining one of triyoga’s Mysore self practice classes, ask for details at your nearest studio. Each branch runs a full time programme. Tom can be found at triyoga Chelsea every weekday, from 6.30 – 9.30am. Click here to view the schedule.