Our next instalment of the triyoga book club with Daniel Simpson begins on Monday, 18th November 2019. Together we’ll explore the Hatha Pradipika, an iconic text about physical yoga (basically a must-read for anyone interested in yoga history). Ahead of this four-week journey, Daniel shares some insights about this classic text. Book club sign-up details are also shared below.

What changed the practice of yoga from seated meditation to something more dynamic? One important source of answers is the Hatha Pradipika, a medieval manual on physical techniques.

Five hundred years before B.K.S. Iyengar’s Light on Yoga (published in 1966), the Hatha Pradipika shed “light on hatha”, to translate its title. The word hatha means “force”, and refers to ways of manipulating energy in the body. Like modern classes, the Hatha Pradipika starts with postures, slowly building up to subtler methods.

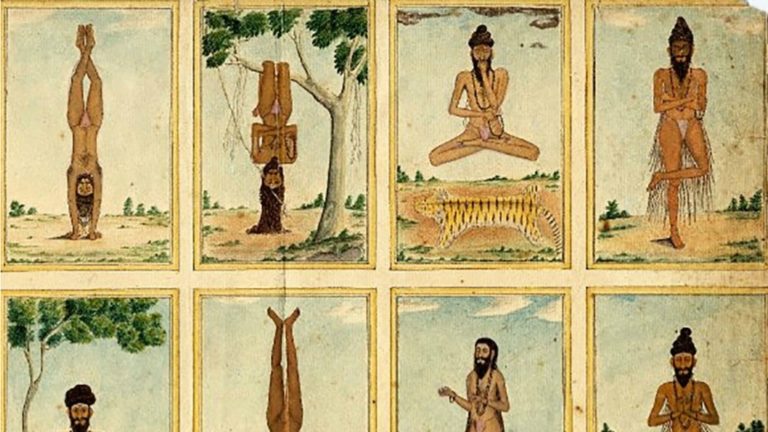

“Asanas are described first because they are the first step of hatha,” the text explains. “They give steadiness, health, and lightness of body.” This emphasis on benefits is relatively new. Earlier texts barely talked about asana, except in terms of sitting still – or performing austerities like standing on one leg for years on end.

The Hatha Pradipika takes a different approach. Among its fifteen postures are two arm-balances (mayurasana and kukkutasana), which are difficult to hold for more than minutes. There is also a forward bend, a twist and a backbend, as well as the resting pose shavasana. Most are described in terms of their positive impacts.

The general aim is transformation. Previously, yogis considered the body a source of distractions, which they had to transcend. However, hatha changed yogic priorities, laying the foundations for modern approaches. Its texts gave accessible instructions, using physical methods to dissolve the mind in meditation.

We’ll explore this in detail at triyoga’s book club, by reading the Hatha Pradipika chapter by chapter. Over four weekly sessions, we’ll learn about the origins of non-seated postures, see the influence of Tantra on yogic ideas about the subtle body and examine the transformative role of breath-control and mudras – two key techniques.

Although renowned for its innovative teachings, the Hatha Pradipika borrows many of its verses from earlier sources. These are compiled to make non-seated asana part of a system that leads to absorption in samadhi, a meditative state beyond the mind, which is also known as the “kingly” raja yoga.

The text’s four chapters describe this progression. Once the body is firm and healthy, the next step is to harness the breath and other inner forces. Pranayama is the key to success, moving energy up the spine to still the mind. Physical methods called “locks” and “seals” (bandhas and mudras) assist in this process.

The ultimate goal is absorption in deep meditation. “I consider those practitioners who only do hatha, without knowing raja yoga, to be labouring fruitlessly,” says the author, the yogi Svatmarama. “Raja yoga will not be complete without hatha, nor hatha without raja yoga. Therefore practise the pair to perfection.”

Daniel Simpson has an MA in Traditions of Yoga and Meditation from SOAS in London. He contributes to triyoga teacher trainings and also runs courses at the Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies.